Hi! Before I get into this, I want to thank everyone who just found me via the publication of my essay, “Thunderbitches and the Whores of Folk” this week in Oldster Magazine. If you haven’t read it yet, I encourage you to do so, because this piece relates directly to that one. In any case, I humbly ask you to please tap the little heart above on the left, and share my essays with anyone you like. Thanks so much, and feel free to leave comments. I love hearing from you and I will respond.

After high school I took a gap year, then attended an elite musical theater conservatory in New York City. The program was brutally demanding but mercifully short, a mere two years, yet each one felt like its own lifetime. I persevered so I would have some professional training under my belt, but secretly I was planning my escape to another galaxy of the performing arts: original music. I had started to write my own songs and play guitar, and I counted the days until I would be free. Making it to graduation felt like running a gauntlet, and I was utterly exhausted. After a few months I returned to my family home in Vancouver to decompress from the whole experience, and plan my next move.

I spent a few weeks sleeping late and catching up with friends over piles of tofu and miso gravy at the Naam, a favorite local restaurant that I’d missed terribly during my time away. All that soothing hippie food and good company revved me right up, and suddenly I was ready to move back to the US and start my life as a singer-songwriter. There was a ton of precedent for Canadian musicians (like the Holy Trinity of Canadian radio: Joni Mitchell, Neil Young and Leonard Cohen) to find big success in America. The only problem was cash. I had almost none, and didn’t relish the thought of going back to retail and restaurant work in the neighborhood. I tied myself in sweaty knots trying to think of a way that I could move back to the US without having to go into debt. But it turned out that I didn’t have to leave my hometown to find American action.

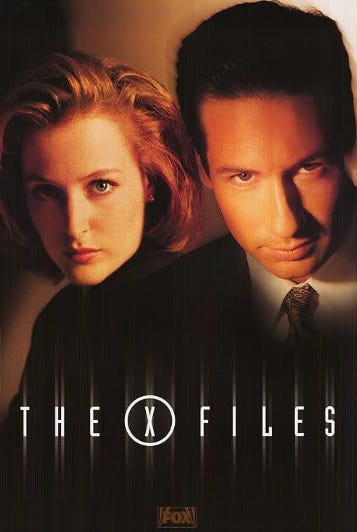

Vancouver in the 90s was called “Hollywood North”, because so many big-budget US films and TV shows were shot there. Some of those include “Intersection” with Sharon Stone and Richard Gere, “Poison Ivy” with Drew Barrymore, and “Bad Company” with Laurence Fishburne and Ellen Barkin. I mention these films in particular because as a background extra I appeared in all of them. Some other notable 90s productions were the TV shows “21 Jump Street”, which often filmed at my high school, “MacGyver”, which Canadians didn’t watch but Americans loved, “Highlander: The Series”, which had a small but dedicated following, and the “The X-Files”, which was an international sensation.

It was a wild and heady era. Movie stars walked among us, and their glamour was intoxicating. All over the city film crews were active day and night, and new talent agencies sprung up to meet the massive demand for background extras, people who could fill in scenes that took place in restaurants, clubs, concerts and schools. Everyone was signing up, not just trained actors and show folk, but anyone who had free time and could make it out to the location of a shoot.

The vetting process to become an extra was minimal. You strolled into an agency, had a Polaroid taken, filled out a form and went home to wait for a call. You never waited long. Your agent would usually ring you that afternoon and tell you to get your ass to some film set the very next morning. If you were low-maintenance and reliable, you could work a lot. If you had US theater training, as I did, you were considered a cut above the masses, and could become an SOC (special on camera). SOCs earned US rates, the most money you could make. You got to feature prominently in a scene, and even interact with the lead actors if you were lucky.

I was not lucky. But I was 21, canny and boldly persistent. I talked my way into an episode of “The X Files” by showing up at my agent’s office every day for two weeks, and making myself indispensable to her. She was a young working mother, ambitious and harried, with a mile-long to-do list and no time for meals. I brought her slices from her favorite pizza place, and fancy coffee from the hotel down the street. I walked her ancient dog, retrieved her mountain of dry cleaning, and even changed her daughter’s diaper a few times, clearing away stacks of headshots from her office couch to do the job.

Eventually she looked up from her desk and said, Hey can you do an American accent? I reminded her that I was fresh from theater school in New York City and could do anything (in truth I was the worst actor in my class, but I wasn’t going to miss this chance, whatever it was). She wrote my name on an agency work order, and told me to bring it to the local Greyhound station next morning at 5am, where “X-Files” would be shooting an episode. She also told me to keep my mouth shut about the job, because she didn’t want to be bombarded by people wanting to appear on the world’s most popular show. I went home and called everyone I knew, blabbing about my impending TV debut, and tossing clothes around my room in an attempt to find a suitable outfit for the job. I wanted to look mature, sophisticated and ferociously gorgeous, like the women on “Living Single”. I chose a sleek black dress with gold buttons down the front, a red paisley scarf tied around my shoulders, and big gold earrings studded with fake but lustrous pearls. Instead of my usual battered Docs I wore my only pair of high heels, which were black and wobbly and shiny enough to reflect any light.

When I arrived on location early the next morning, I was sent straight to wardrobe, stripped of my clothes and jewelry, and outfitted in the distinctly unglamorous uniform of female Greyhound staff members. It was a navy blue knee-length skirt, a starchy white blouse buttoned all the way up to the collar, and a narrow navy blue scarf tied around my neck. The whole thing was primarily polyester, and I steeled myself for a very itchy day.

Once properly costumed I was brought to the set and introduced to a girl I’ll call Jenny, who was to play my co-worker in the scene. She was a singer from Antigua, with high cheekbones and huge brown eyes that sparkled madly. She had recently gotten a music degree and was looking to launch her singing career as soon as possible, so we had a lot in common. We agreed that acting was just our side hustle. But Jenny was naturally good at it, and the camera loved her, so she got a lot of SOC work. She knew the ropes, and I was grateful to work alongside someone so confident.

The two of us were placed behind the customer-service counter in the station, where people line up to buy tickets before boarding a bus. The Director, who looked interchangeable with every other TV director of the era (white, sweaty, jean-jacketed and baseball-capped), came over and began to do his thing. Waving his arms like he was conducting an orchestra, he told us to keep our heads down and focus on the small, clunky computers in front of us, but not to actually type on the keys, because the sound would be dubbed in later. When we were approached by someone in the scene (who?), we should do exactly what he asked. Other than that, he said, just smile and stick your tits out. Then he turned on his heel and walked back to the far corner of the room, where people were fussing over a man whose back was turned to us. The Director threw his arm around the man and began to whisper furiously in his ear, like a coach ramping up his star player. The level of volume and activity on set suddenly spiked.

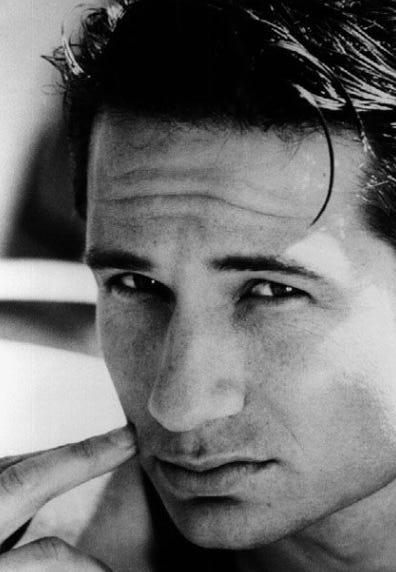

That’s when the mysterious man turned around, and I realized that Jenny and I were about to do a scene with Fox Mulder himself, David Duchovny.

The Assistant Director sprinted toward us and started barking orders to the film crew, who snapped to attention and readied the lights and camera for the scene. The Director walked Duchovny over, and as they approached I could see the actor’s sweatshirt and jeans were hidden underneath a big black overcoat, the very same one I’d seen him wear in every “X-Files” episode. As with all actors he was thinner than he looked on screen, and a bit shorter. He also had that uniquely masculine scruffiness that is wickedly sexy, and although his face looked tired and wan, his lips were full and pouty, and somehow beckoning even when he frowned. In short, he looked wildly kissable, and I had a hard time thinking of anything else when he stood in front of us.

The episode we were filming hinged on a city-wide man-hunt for someone who had gone missing, and was being sought by the FBI. According to the Director, Agent Mulder was going to burst into the bus station with a picture of the missing man in his hand, and ask us if we had seen him in the bus station. We were supposed to stare intently at the picture, then shake our heads no. The whole exchange was going to take about 15 seconds, and it would be shot twice: once from behind us, so you could see Mulder’s inquiry and the photo, then again over his shoulder, so you could see our reactions.

Here I will mention that I have a special talent which makes up for a lot of missing acting skills: I can make it seem like I’m deeply absorbed in something, when in fact I’m completely alert and aware of everything that’s going on around me. This actually comes in very handy as a writer, because I can eavesdrop on all kinds of conversations without anyone perceiving me as a threat. I’ll be gazing at a book or my phone, but I’m actually listening intently to your convo. If you happen to catch me, I’m good at appearing surprised, and I do a particularly convincing fake-out, looking up from whatever I’m doing as if to say, Sorry, were you talking to me?

Before the cameras started rolling, the three of us practiced the scene to get the timing right. When Duchovny approached with the picture and said, Excuse me, have you seen this man I employed my fake-out technique. The Director liked it so much that he made the actor say his line directly to me, so he could have something to work with in the scene. Holy shit: Mulder and I were going to connect. I reminded myself to stay calm and refrain from pouncing on his mouth.

Once the Director called action! he strolled off and began studying a clipboard with shot lists for the next scene. The camera rolled. Jenny, me and Duchovny did our thing, and it went off without a hitch. We did it again, for the other angle, and it was done. I hugged Jenny goodbye and got a ride home with a lighting grip. When he pulled up in front of my house, he looked me in the eye and told me to enjoy this moment, because not many people get to appear on a famous network TV show that everyone can watch.

My house, however, didn’t have a TV set, so on the night the episode finally aired I went over to a neighbor's place to view my debut. Sitting on her couch, staring at her Dad’s old brown Zenith, I jittered a bowl of popcorn on my lap until the Greyhound scene started. Then it happened: Mulder entered the station, ran up to the counter, held up the picture, and asked his question. Jenny shook her lovely head, and the camera moved on.

Reader, I had been completely cut from the scene. Not a single trace of my presence remained, I might as well have not even shown up for the job. It was so mortifying that I didn’t leave my house for days. I took no phone calls, and didn’t even get the mail from the front porch. I stayed in my room eating corn chips and peanut butter, listening to Sinead O’Connor songs on my Walkman and nursing my shame.

On day 5 a family friend, who was a working actor and had a ton of TV experience, left a package on my doorstep. It was a huge pair of steely black scissors, with a note attached: Hey lady: don’t let the bastards cut you down! I kept the scissors, but I gave up acting shortly after that. Let someone else make-out with Mulder. It was enough that I’d gotten a chance. Once my “X-Files” check cleared I had good strong American dollars in my pocket. I also had 15 original songs that were begging to be set free into the world. I had to get back on track, back to the US. If I was going to be rejected, at least it would be on my own terms (and that, in case you didn’t know, is the battle cry of an artist, and you can fucking quote me).

You can learn more about my job as a Power Voice coach for women HERE.

Hey fam: Force Majeure is a reader-supported publication. It’s the ONLY place on the whole entire Internet where I talk about deeply personal things, share hard-won wisdom, and celebrate people and ideas worth knowing. The most deeply personal sh** is behind a paywall, so if you like what you’ve read and want to go deeper with me, I invite you to subscribe:

Omg I was cut out of 90210 but still get residual checks. That was a real job that I auditioned for and had two lines, etc. I feel your pain. I got more screen time (and even lines dubbed in) when I was extra on My So Called Life (the pilot) and got pulled to be featured. I even ended up in the opening credits so my face was there for every airing. Didn’t get residuals for that one, though.

Anyway, I’ve loved reading both of your pieces and look forward to more. Glad I discovered you. :)